How does the URL for my resource should look like? Plural or singular nouns? How many URLs do I need for one resource? What HTTP method on which URL do I use for creating a new resource? Where should I place optional parameter? What about URLs for operations that don’t involve resources? What is the best approach for pagination or versioning? Designing RESTful APIs can be tricky because there are so many possibilities. In this post, we take a look at RESTful API design and point out best practices.

Use Two URLs per Resource

One URL for the collection and one for a certain element:

/employees #collection URL

/employees/56 #element URL

Use Nouns instead of Verbs for Resources

This will keep you API simple and the number of URLs low. Don’t do this:

/getAllEmployees

/getAllExternalEmployees

/createEmployee

/updateEmployee

Instead…

Use HTTP Methods to Operate on your Resources

GET /employees

GET /employees?state=external

POST /employees

PUT /employees/56

Use URLs to specify the resources you want to work with. Use the HTTP methods to specify what to do with this resource. With the four HTTP methods GET, POST, PUT, DELETE you can provide CRUD functionality (Create, Read, Update, Delete).

- Read: Use GET for reading resources. GET requests never ever change the state of the resource. No side effects. GET is idempotent. The GET method has a read-only semantic. Consequently, you can cache the calls perfectly.

- Create: Use POST for creating new resources.

- Update: Use PUT for updating existing resources.

- Delete: Use DELETE for deleting existing resources.

2 URLs multiplied by 4 HTTP methods equals a nice set of functionality. Take a look at this matrix:

| POST (Create) | GET (Read) | PUT (Update) | DELETE (Delete) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

/employees |

Creates a new employee | Lists all employees | Batch update employees | Delete all employees |

/employees/56 |

(Error) | Show details of the employee 56 | Update the employee 56 | Delete the employee 56 |

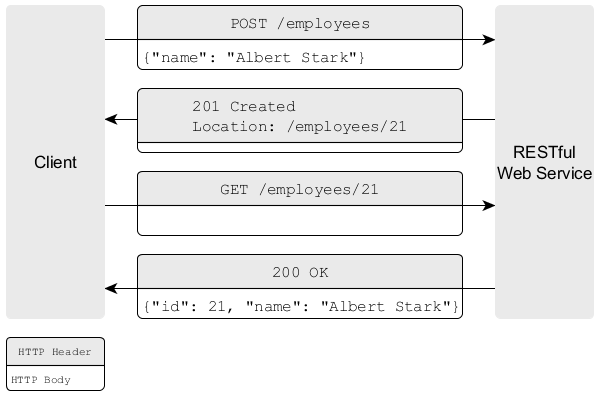

Use POST on Collection-URL for Creating a New Resource

How could a client-server interaction for creating a new resource look like?

Use POST on collection-URL for creating a new resource

- The client sends a POST request to the collection URL

/employees. The HTTP body contains the attributes of the new resource “Albert Stark”. - The RESTful web service generates an ID for the new employee, creates the employee in its internal model and sends a response to the client. This response contains a Location HTTP header that indicates the URL under which the created resource is accessible.

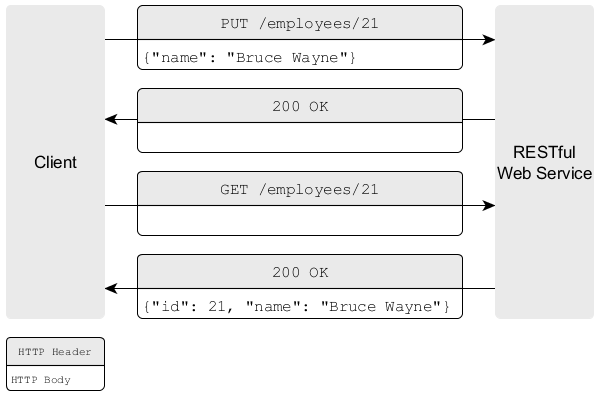

Use PUT on Element-URL for Updating a Resource

Use PUT for updating an existing resource.

- The client sends a PUT request to the element URL

/employee/21. The HTTP body of the request contains the updated attribute values (the new name “Bruce Wayne” of the employee 21). - The REST service updates the name of the employee with the ID 21 and confirms the changes with the HTTP status code 200.

Use Consistently Plural Nouns

Prefer

/employees

/employees/21

over

/employee

/employee/21

Indeed, it’s a matter of taste, but the plural form is more common. Moreover, it’s more intuitive, especiallyes GET /employees?state=external POST /employees PUT /employees/56 when using GET on the collection URL. But most important: avoid mixing plural and singular nouns, which is confusing and error-prone.

Use the Query String (?) for Optional or Complex Parameter.

Don’t do this:

GET /employees

GET /externalEmployees

GET /internalEmployees

GET /internalAndSeniorEmployees

Keep your URLs simple and the URL set small. Choose one base URL for your resource and stick to it. Move complexity or optional parameters to the query string.

GET /employees?state=internal&maturity=senior

Use HTTP Status Codes

The RESTful Web Service should respond to a client’s request with a suitable HTTP status response code.

2xx– success – everything worked fine.4xx– client error – if the client did something wrong (e.g. the client sends an invalid request or he is not authorized)5xx– server error – if the server did something wrong (e.g. error while trying to process the request)

Consider the HTTP status codes on Wikipedia. However, be aware, that using all of them could be confusing for the users of your API. Keep the set of used HTTP status codes small. It’s common to use the following:

| 2xx: Success | 3xx: Redirect | 4xx: Client Error | 5xx: Server Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200 OK 201 Created |

301 Moved Permanently 304 Not Modified |

400 Bad Request 401 Unauthorized 403 Forbidden 404 Not Found |

500 Internal Server Error |

Provide Useful Error Messages

Additionally to an appropriate status code, you should provide a useful and verbose description of the error in the body of your HTTP response. Here’s an example.

Request:

GET /employees?state=super

Response:

// 400 Bad Request

{

"message": "You submitted an invalid state. Valid state values are 'internal' or 'external'",

"errorCode": 352,

"additionalInformation" : "http://www.domain.com/rest/errorcode/352"

}

Use CamelCase for Attribute Names

Use CamelCase for your attributes identifiers.

{ "yearOfBirth": 1982 }

Don’t use underscores (year_of_birth) or capitalize (YearOfBirth). Often your RESTful web service will be consumed by a client written in JavaScript. Typically the client will convert the JSON response to a JavaScript

object (by calling var person = JSON.parse(response) ) and call its attributes. Therefore, it’s a good idea to stick to the JavaScript convention which makes the JavaScript code more readable and intuitive. Compare

person.year_of_birth //violates JavaScript convention

person.YearOfBirth //suggests constructor method

with

person.yearOfBirth //nice!

Always Include a Mandatory Version Number in your URLs

Always release your RESTful API with a version number. Place the version number in your URL to make it mandatory. This makes it easier for you to evolve your API if you have incompatible and breaking changes. Just release the new API under an increased version number. Hence, clients can migrate to your new API at their own speed. They are not forced or get into troubles because they are suddenly using the new API which behaves differently.

Use the intuitive “v” prefix to signal that the following number is a version number.

/v1/employees

You don’t need a minor version number (“v1.2”), since you shouldn’t change your API that frequently. But your implementation can be improved constantly as long as you don’t change your API or its documented semantics.

Provide Pagination

It is almost never a good idea to return all resources of your database at once. Consequently, you should provide a pagination mechanism. It is common to use the parameters offset and limit, which are well-known from databases.

/employees?offset=30&limit=15 #returns the employees 30 to 45

If the client omits the parameter you should use defaults. Don’t return all resources. A good default is offset=0 and limit=10. If the retrieval is more expensive you should decrease the limit.

/employees #returns the employees 0 to 10

Moreover, if you use pagination, a client needs to know the total number of resources. Example:

Request:

GET /employees

Response:

{

"offset": 0,

"limit": 10,

"total": 3465,

"employees": [

//...

]

}

Use Verbs for Non-Resource Responses

Sometimes a response to an API call doesn’t involve resources (like calculate, translate or convert). Example:

GET /translate?from=de_DE&to=en_US&text=Hallo

GET /calculate?para2=23¶2=432

In this case, your API doesn’t return any resources. Instead, you execute an operation and return the result to the client. Hence, you should use verbs instead of nouns in your URL to distinguish clearly the non-resource responses from the resource-related responses.

Consider Resource-Specific and Cross-Resource Search

Providing a search for resources of a specific type is easy. Just use the corresponding collection URL and append the search string in a query parameter.

GET /employees?query=Paul

If you want to provide a global search across all resources, you need a different approach. Remember the lesson about non-resource URLs: Use verbs instead of nouns. Hence, your search URL could look like the following:

GET /search?query=Paul //returns employees, customers, suppliers etc.

Provide Links for Navigating through your API (HATEOAS)

Ideally, you don’t let your clients construct URLs for using your REST API. Let’s consider an example.

A Client wants to access the salary statements of an employee. For that he has to know that he can access the salary statements by appending the string “salaryStatements” to the employee URL (e.g. /employees/21/salaryStatements).

This string concatenation is error-prone, fragile and hard to maintain. If you change the way to access the salary statement in your REST API (e.g. using now “salary-statements” or “paySlips”) all clients will break.

It’s better to provide links in your response which the client can follow. Example:

Request:

GET /employees/

Response:

//...

{

"id":1,

"name":"Paul",

"links": [

{

"rel": "salary",

"href": "/employees/1/salaryStatements"

}

]

},

//...

If the client exclusively relies on the links to get the salary statement, he won’t break if you change your API, since the client will always get a valid URL (as long as you update the link in case of URL changes). Another benefit is that your API becomes more self-descriptive and less documentation is necessary.

When it comes to pagination you can also provide links for getting the next or previous page. Just provide links with the appropriate offset and limit.

GET /employees?offset=20&limit=10

{

"offset": 20,

"limit": 10,

"total": 3465,

"employees": [

//...

],

"links": [

{

"rel": "nextPage",

"href": "/employees?offset=30&limit=10"

},

{

"rel": "previousPage",

"href": "/employees?offset=10&limit=10"

}

]

}

Further Readings

- I wrote a post about Best Practices for Testing RESTful Services in Java.

- I highly recommend Brain Mulloy’s nice paper, which serves as the base of this post.