TDD 的神话

传说中 TDD 是一种能驱动设计的方法。使用了TDD,你就能神功附体,各种设计都可以文思如泉涌,喷薄而来。很不幸,你被忽悠了。TDD让你自动获得设计的能力,是一种错觉。

以 Game Of Life 的题目为例子。规则就三条

- 如果周围的邻居有三个是活的,那么我就活的,无论现在是生还是死

- 如果周围的邻居有两个是活的,那么我现在是活的,就还是活的。如果我现在是死的,就还是死的。

- 其余情况,我都会被弄死

- 如果是在棋盘的边缘,则认为棋盘外的格子都是死的状态

下面的实现被保存在了 github 上:taowen/game-of-life

经典的理论,通过给定不同的输入和输出,逐步地通过TDD把代码给写出来。我们来尝试一下

t.Run("==3", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{true, true, true},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 1, 1)

should.True(output[1][1])

})

第一个测试是 happy path,给定周围的邻居有三个是活的。那么我应该被变成活的。这个测试里的,测的就是中间的那个cell的情况。

func runOneCycle(input [][]bool, output [][]bool, x int, y int) {

aliveNeighbours := countAliveNeighbours(input, x, y)

if aliveNeighbours == 3 {

output[x][y] = true

}

}

func countAliveNeighbours(input [][]bool, x int, y int) int {

count := 0

if input[x - 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x - 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x - 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

if input[x][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x][y + 1] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

return count

}

然后,我们给定第二个输入条件

t.Run("dead ==2 dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, true, true},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 1, 1)

should.False(output[1][1])

})

t.Run("alive ==2 alive", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, true, true},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 1, 1)

should.True(output[1][1])

})

对应的实现也就多了一条规则

func runOneCycle(input [][]bool, output [][]bool, x int, y int) {

aliveNeighbours := countAliveNeighbours(input, x, y)

if aliveNeighbours == 3 {

output[x][y] = true

} else if aliveNeighbours == 2 {

output[x][y] = input[x][y]

}

}

然后继续这个过程

t.Run("otherwise, dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, true, false},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 1, 1)

should.False(output[1][1])

})

于是乎

func runOneCycle(input [][]bool, output [][]bool, x int, y int) {

aliveNeighbours := countAliveNeighbours(input, x, y)

if aliveNeighbours == 3 {

output[x][y] = true

} else if aliveNeighbours == 2 {

output[x][y] = input[x][y]

} else {

output[x][y] = false

}

}

所以,我们通过变换不如的出入输出条件,把各种规则判断都实现了出来了。通过 TDD 我们完成了设计。

接下来就是演示什么叫重构

t.Run("top edge", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, true, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 0, 1)

should.False(output[0][1])

})

对应的计算活着的邻居数的代码就得更新一下了,要不然数组访问会越界

func countAliveNeighbours(input [][]bool, x int, y int) int {

count := 0

if x > 0 {

if input[x - 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x - 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x - 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

}

if input[x][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x][y + 1] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

return count

}

继续这个迭代过程

t.Run("left edge", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{true, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

}

output := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

}

runOneCycle(input, output, 0, 0)

should.False(output[0][0])

})

然后接着对 countAliveNeighbours 打补丁

func countAliveNeighbours(input [][]bool, x int, y int) int {

count := 0

if x > 0 {

if y > 0 {

if input[x - 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

}

if input[x - 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x - 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

}

if y > 0 {

if input[x][y - 1] {

count++

}

}

if input[x][y + 1] {

count++

}

if y > 0 {

if input[x + 1][y - 1] {

count++

}

}

if input[x + 1][y] {

count++

}

if input[x + 1][y + 1] {

count++

}

return count

}

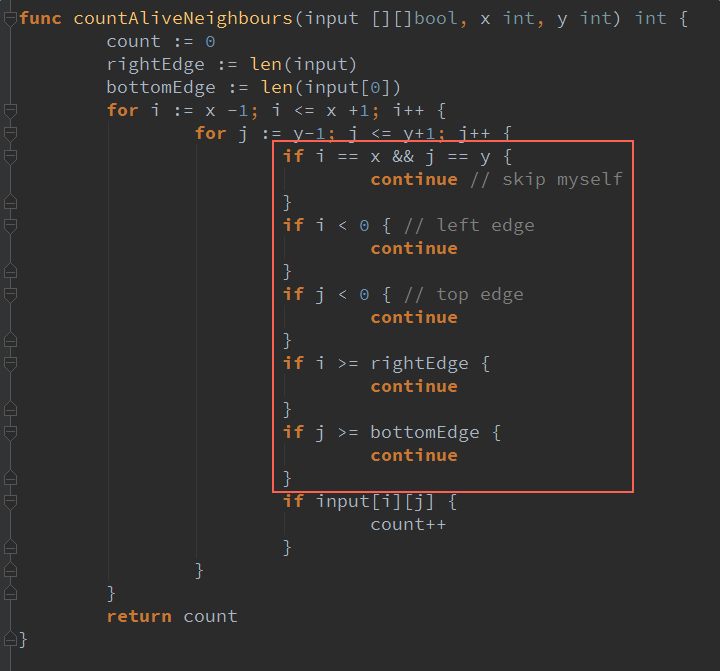

你看那!你看那!代码就是这样腐坏哒

来,我们重构大神拯救你。先补一点单元测试吧

func Test_countAliveNeighbours(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("all true", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

}

should.Equal(8, countAliveNeighbours(input, 1, 1))

should.Equal(5, countAliveNeighbours(input, 0, 1))

should.Equal(3, countAliveNeighbours(input, 0, 0))

})

}

func countAliveNeighbours(input [][]bool, x int, y int) int {

count := 0

rightEdge := len(input)

bottomEdge := len(input[0])

for i := x -1; i x +1; i++ {

for j := y-1; j y+1; j++ {

if i == x && j == y {

continue // skip myself

}

if i < 0 { // left edge

continue

}

if j < 0 { // top edge

continue

}

if i >= rightEdge {

continue

}

if j >= bottomEdge {

continue

}

if input[i][j] {

count++

}

}

}

return count

}

然后为了保证100%的测试覆盖率,我们多加一些测试

func Test_countAliveNeighbours(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("all true", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

}

expect := [][]int{

{3, 5, 3},

{5, 8, 5},

{3, 5, 3},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], countAliveNeighbours(input, i, j))

}

}

})

t.Run("all false", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

}

expect := [][]int{

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], countAliveNeighbours(input, i, j))

}

}

})

}

这样我们就通过 TDD 一步步驱动出了我们的设计。最终完整的实现代码是

func runOneCycle(input [][]bool, output [][]bool, x int, y int) {

aliveNeighbours := countAliveNeighbours(input, x, y)

if aliveNeighbours == 3 {

output[x][y] = true

} else if aliveNeighbours == 2 {

output[x][y] = input[x][y]

} else {

output[x][y] = false

}

}

func countAliveNeighbours(input [][]bool, x int, y int) int {

count := 0

rightEdge := len(input)

bottomEdge := len(input[0])

for i := x -1; i <= x +1; i++ {

for j := y-1; j <= y+1; j++ {

if i == x && j == y {

continue // skip myself

}

if i < 0 { // left edge

continue

}

if j < 0 { // top edge

continue

}

if i >= rightEdge {

continue

}

if j >= bottomEdge {

continue

}

if input[i][j] {

count++

}

}

}

return count

}

但是这个设计真的是驱动而来的么?

问题一,给定下面这个实现

问题二,为什么是以一个格子为中心,计算它周围一圈的邻居?

这样每一个格子都会作为很多各自的邻居被重复地判断。为什么不是这样的行进过程?

然后这样?

每个格子都帮自己的邻居把我自己是生还是死告诉它,然后走完一圈下来,每个格子都知道了自己邻居有几个是活着的了。

这道题如果作为考察减少cpu比较指令的使用量,会得出完全不一样的解法。作为考察对象设计与cache miss的关系的时候,又会得出完全不一样的解法。TDD 不能帮你做设计。TDD 只是在你已经设计好了之后,辅助你把你的设计落实到纸面上而已。

TDD 的理想

还是 Game Of Life的题目,这次我们用另外一个方法来实现。先写测试

func Test_notifyNeighbours(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("central", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cells := createCells([][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, false, false},

})

notifyNeighbours(cells, 1, 1)

should.Equal(1, cells[0][0].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(1, cells[2][2].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(0, cells[1][1].aliveNeighboursCount)

})

}

这次的计算方式改了,不再是主动计算我周围一圈的邻居的状态。而是每个邻居告诉我,他们自己是否活过来了,或者死去了。

用于描述棋盘的数据结构是这样定义的

type Cell struct {

wasAlive bool

isAlive bool

aliveNeighboursCount int

}

func createCells(states [][]bool) [][]Cell {

cells := make([][]Cell, len(states))

for i := 0; i < len(states); i++ {

cells[i] = make([]Cell, len(states[i]))

for j :=0; j < len(states[i]); j++ {

cells[i][j] = Cell{

wasAlive: false,

isAlive: states[i][j],

aliveNeighboursCount: 0,

}

}

}

return cells

}

然后写一个实现,通过上面的测试:

func (cell *Cell) justRevived() bool {

return !cell.wasAlive && cell.isAlive

}

func (cell *Cell) notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived() {

cell.aliveNeighboursCount++

}

func notifyNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int) {

if cells[x][y].justRevived() {

cells[x-1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x-1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x-1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

}

}

接下来测试死去的情况

t.Run("central revived=>died", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cells := createCells([][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, false, false},

})

notifyNeighbours(cells, 1, 1)

should.Equal(1, cells[0][0].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(1, cells[2][2].aliveNeighboursCount)

cells[1][1].isAlive = false

notifyNeighbours(cells, 1, 1)

should.Equal(0, cells[0][0].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(0, cells[2][2].aliveNeighboursCount)

})

这里测试的情况是中间的,先活过来了,然后又死去了,对周围的影响。对应的实现代码

func (cell *Cell) justRevived() bool {

return !cell.wasAlive && cell.isAlive

}

func (cell *Cell) justDied() bool {

return cell.wasAlive && !cell.isAlive

}

func (cell *Cell) notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived() {

cell.aliveNeighboursCount++

}

func (cell *Cell) notifyThereIsNeighbourDied() {

cell.aliveNeighboursCount--

}

func notifyNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int) {

if cells[x][y].justRevived() {

cells[x][y].wasAlive = true

cells[x-1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x-1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x-1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

cells[x+1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

} else if (cells[x][y].justDied()) {

cells[x][y].wasAlive = false

cells[x-1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x-1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x-1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x+1][y-1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x+1][y].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

cells[x+1][y+1].notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

}

}

然后我们进行重构

func visitNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int, visitor func(neighbour *Cell)) {

visitor(&cells[x-1][y-1])

visitor(&cells[x-1][y])

visitor(&cells[x-1][y+1])

visitor(&cells[x][y-1])

visitor(&cells[x][y+1])

visitor(&cells[x+1][y-1])

visitor(&cells[x+1][y])

visitor(&cells[x+1][y+1])

}

func notifyNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int) {

if cells[x][y].justRevived() {

cells[x][y].wasAlive = true

visitNeighbours(cells, x, y, func(neighbour *Cell) {

neighbour.notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

})

} else if (cells[x][y].justDied()) {

cells[x][y].wasAlive = false

visitNeighbours(cells, x, y, func(neighbour *Cell) {

neighbour.notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

})

}

}

然后我们来测试边缘的情况

t.Run("edge", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cells := createCells([][]bool{

{false, true, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

})

notifyNeighbours(cells, 0, 1)

should.Equal(1, cells[0][0].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(1, cells[1][1].aliveNeighboursCount)

should.Equal(0, cells[2][2].aliveNeighboursCount)

})

然后写两套border的实现

type Border interface {

visitNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int, visitor func(neighbour *Cell))

}

type EdgeBorder struct {

}

func (border *EdgeBorder) visitNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int, visitor func(neighbour *Cell)) {

rightEdge := len(cells)

bottomEdge := len(cells[0])

for i := x - 1; i <= x + 1; i++ {

for j := y - 1; j <= y + 1; j++ {

if i == x && j == y {

continue // skip myself

}

if i < 0 {

// left edge

continue

}

if j < 0 {

// top edge

continue

}

if i >= rightEdge {

continue

}

if j >= bottomEdge {

continue

}

visitor(&cells[i][j])

}

}

}

type FullBorder struct {

}

func (border *FullBorder) visitNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int, visitor func(neighbour *Cell)) {

visitor(&cells[x - 1][y - 1])

visitor(&cells[x - 1][y])

visitor(&cells[x - 1][y + 1])

visitor(&cells[x][y - 1])

visitor(&cells[x][y + 1])

visitor(&cells[x + 1][y - 1])

visitor(&cells[x + 1][y])

visitor(&cells[x + 1][y + 1])

}

对于边缘的cell,创建不同的border

type Cell struct {

wasAlive bool

isAlive bool

aliveNeighboursCount int

border Border

}

func createCells(states [][]bool) [][]Cell {

cells := make([][]Cell, len(states))

for i := 0; i < len(states); i++ {

cells[i] = make([]Cell, len(states[i]))

for j := 0; j < len(states[i]); j++ {

cells[i][j] = Cell{

wasAlive: false,

isAlive: states[i][j],

aliveNeighboursCount: 0,

border: nil,

}

if i == 0 || i == len(states) - 1 || j == 0 || j == len(states[i]) - 1 {

cells[i][j].border = &EdgeBorder{}

} else {

cells[i][j].border = &FullBorder{}

}

}

}

return cells

}

这样,我们的 notifyNeighbours 的实现就变成了

func notifyNeighbours(cells [][]Cell, x int, y int) {

myself := &cells[x][y]

if myself.justRevived() {

myself.wasAlive = true

myself.border.visitNeighbours(cells, x, y, func(neighbour *Cell) {

neighbour.notifyThereIsNeighbourRevived()

})

} else if myself.justDied() {

myself.wasAlive = false

myself.border.visitNeighbours(cells, x, y, func(neighbour *Cell) {

neighbour.notifyThereIsNeighbourDied()

})

}

}

自此,就解决了计算邻居有几个是活着的问题。

第二个目标是计算自己当前是否isAlive

func Test_updateIsAlive(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 3

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.True(cell.isAlive)

}

实现

func (cell *Cell) updateIsAlive() {

if cell.aliveNeighboursCount == 3 {

cell.isAlive = true

}

}

测试

t.Run("alive == 2 alive", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = true

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 2

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.True(cell.isAlive)

})

t.Run("dead == 2 dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = false

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 2

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.False(cell.isAlive)

})

实现

func (cell *Cell) updateIsAlive() {

if cell.aliveNeighboursCount == 3 {

cell.isAlive = true

} else if cell.aliveNeighboursCount == 2 {

cell.isAlive = cell.wasAlive

}

}

测试

t.Run("otherwise, dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = true

cell.isAlive = true

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 1

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.False(cell.isAlive)

})

实现

func (cell *Cell) updateIsAlive() {

if cell.aliveNeighboursCount == 3 {

cell.isAlive = true

} else if cell.aliveNeighboursCount == 2 {

cell.isAlive = cell.wasAlive

} else {

cell.isAlive = false

}

}

最后,我们把前面两个功能组合起来,实现完整的计算一帧生命的游戏的算法

func Test_runOneCycle(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cells := createCells([][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{true, true, true},

})

runOneCycle(cells)

expect := [][]bool {

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, true, false},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], cells[i][j].isAlive, fmt.Sprintf("%v,%v", i, j))

}

}

}

实现

func runOneCycle(cells [][]Cell) {

for i := 0; i < len(cells); i++ {

for j := 0; j < len(cells[i]); j++ {

notifyNeighbours(cells, i, j)

}

}

for i := 0; i < len(cells); i++ {

for j := 0; j < len(cells[i]); j++ {

cells[i][j].updateIsAlive()

}

}

}

这里的实现还可以改进,两次遍历可以缩短为一次遍历。在通知完neighbour之后,左上角的邻居的死活已经可以立即确定了。

我在这里花这么多篇幅,不是去证明这个题可以以更少的计算量完成。而是,我们观察一下两轮下来写出来的测试。这是第一轮的测试:

func Test_countAliveNeighbours(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("all true", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

{true, true, true},

}

expect := [][]int{

{3, 5, 3},

{5, 8, 5},

{3, 5, 3},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], countAliveNeighbours(input, i, j))

}

}

})

t.Run("all false", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

input := [][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

}

expect := [][]int{

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], countAliveNeighbours(input, i, j))

}

}

})

}

请问这样的测试如何来保障第二种实现的正确性?当然是用不了的,当实现改变了,之前的测试就要被废弃掉。

再来看第二轮的测试

func Test_updateIsAlive(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("== 3", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 3

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.True(cell.isAlive)

})

t.Run("alive == 2 alive", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = true

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 2

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.True(cell.isAlive)

})

t.Run("dead == 2 dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = false

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 2

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.False(cell.isAlive)

})

t.Run("otherwise, dead", func(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cell := Cell{}

cell.wasAlive = true

cell.isAlive = true

cell.aliveNeighboursCount = 1

cell.updateIsAlive()

should.False(cell.isAlive)

})

}

这么一大片的测试可以用于保障第一种实现的正确吗?显然也是不能的,如果我们要切换实现,这一片测试也要被抛弃掉。

再来看第三种测试

func Test_runOneCycle(t *testing.T) {

should := require.New(t)

cells := createCells([][]bool{

{false, false, false},

{false, false, false},

{true, true, true},

})

runOneCycle(cells)

expect := [][]bool {

{false, false, false},

{false, true, false},

{false, true, false},

}

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

should.Equal(expect[i][j], cells[i][j].isAlive, fmt.Sprintf("%v,%v", i, j))

}

}

}

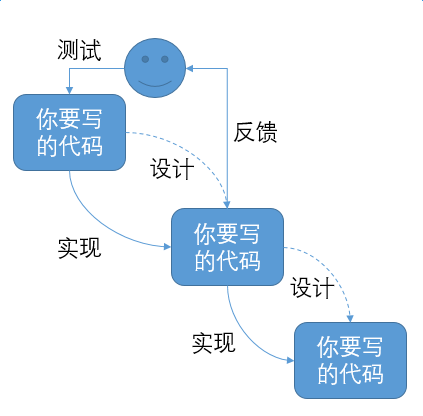

这个测试的行为是稳定的。无论是第一种实现,还是第二种实现,稍加改动都可以复用。如果可能,尽可能以稳定的需求边界去测试驱动实现。这样积累下来的测试更有机会在重构的时候用于保证对外行为的不变。

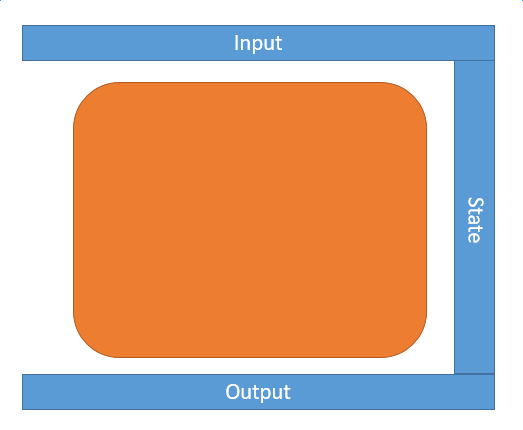

TDD 的理想很简单。如果我们可以积累一系列测试来测试一个复杂行为的输入输出,那么我们就拥有了尝试各种实现的自由。越是复杂的行为,越是要尽可能地把测试写到最顶层,而不是细粒度的单元测试。

之前的实现

TDD 的苟且

TDD 是一种然而并没有什么卵用的技术。不用你们说了,我帮你们把心里话给说出来了。基于以下原因:

- 具有比较复杂的业务规则的场景非常少。大部分人找不到TDD适用的经典场景。

- 人为设定的规则正逐步让位于机器学习等基于数据的系统。复杂业务逻辑的用武之地被进一步打压。

- 经典的TDD是在一个进程内的单一语言内实施的。软件开发的经典粒度从一个语言里的对象,变成了多种语言编写的微服务。

- 测试数据的准备没有系统化地理论,大部分初学者在这步就已经被吓跑了

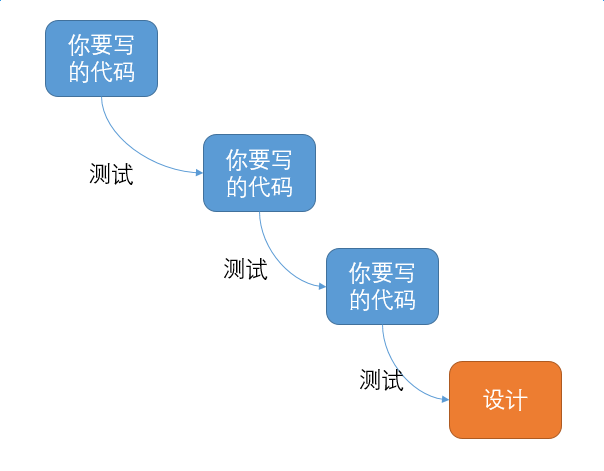

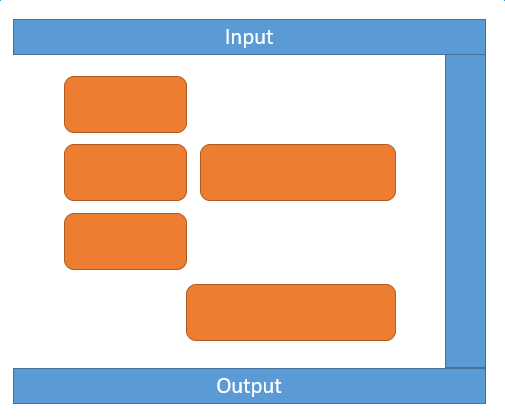

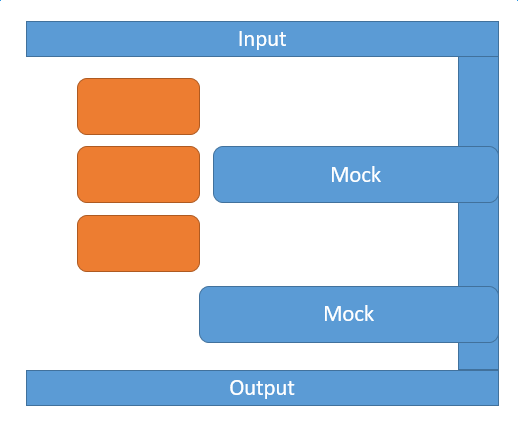

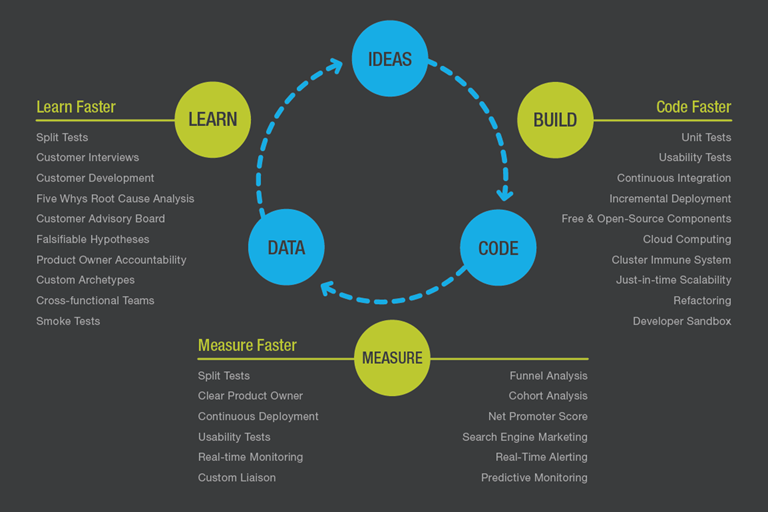

在稍微有点规模的业务系统里实施 TDD 都会发现,我们会变成这样的模式

当现代的架构已经越来越多地使用进程作为单元来装配业务逻辑的时候,TDD 并没有能够与时俱进。在各种语言,各种框架,各种乱七八糟的代码上,找到可 Mock 的点,插入 Mock 逻辑是一件让人心力憔悴的事情。这些 Mock 一点都不通用,而且很容易因为代码的调整,而使得 Mock 失效。根本就没有一个跨框架,跨语言,跨平台的方法去mock掉http的调用,thrift的调用。

对于测试数据准备问题

- 调用的输入数据

- 调用的返回数据

- 以及调用在处理过程中所基于的状态

所谓的状态就是在处理过程中请求的外部服务。在稍微复杂一点的遗留系统上,手工去构造这三份数据都是非常非常困难的。

有复杂逻辑的代码是很少的。大部分的业务代码不过是砖头的搬运。各种bug往往出现在“导线的接头处”。

TDD 的诗与远方

TDD 需要进一步地发展。TDD 的理念是光辉不朽的。

编写测试

运行测试,挂了,红色

写实现

再运行测试,又挂了,看原因

修改实现

再运行测试,OK了,绿色

写下一个测试

这种红绿红绿的节奏感是所有挣扎在焦油坑里的人们所向往的。为什么会一线的开发人员会喜欢这种红绿的节奏呢?

- 边开发,边跑测试

- 开发完了,提交之前跑个测试

- 提交之后,在线下环境跑个测试

- 小流量上线

- 线上开白名单

- 线上双写,log比对

- 线上用特性开关,逐步切流量

所有这些措施,都是反馈机制的一种。而TDD作为反馈周期最短的反馈实践方式,是用起来最爽的。没有什么比让我的代码在IDE里可验证更能提高码农的幸福感,加薪都比不上。假想一下,如果你的代码在本地无法执行,甚至线下都没有一个完整的环境。即便有完整的环境,也没有完整的运营配置产品配置数据,导致行为和线上不一样。那么你每天能干的事情就是

- 写代码。把自己改的那几行代码单独跑一下,保证基本的PHP ERROR没有。

- 把本地的测试代码和数据comment掉,提交。小流量上线,祈祷不要挂

- 然后开一点点流量,看log

- 发现有问题,本地再改改。再次小流量

- 发现前面有人在上线,排队个两个小时,终于轮到我再来试一轮了

在这种随时自己的代码会引起大问题的精神压力下,你让我们要持续重构?拥抱变化?不会的

个体做事的成本决定了个体的做事态度。没有安全网机制保障下的RD,只会做最正确的事情,那就是:

把代码拷贝一份,我在新的函数里写我新的业务逻辑

因为我没有安全感,我没有办法在线下,在IDE里快速地验证代码的修改。而给代码加单元测试,Mock网络通信,准备测试数据,即便节操值几个钱,也不值那么多钱。

TDD是有价值的,只是成本太高

TDD的未来之路在哪里?如何降低成本?我能想到三个措施

- 把测试放到线上去跑。避免了搭环境的成本,避免了把线上的配置导到线下的成本。需要解决的难点是在线上跑测试的副作用怎么被收集到独立的区域。

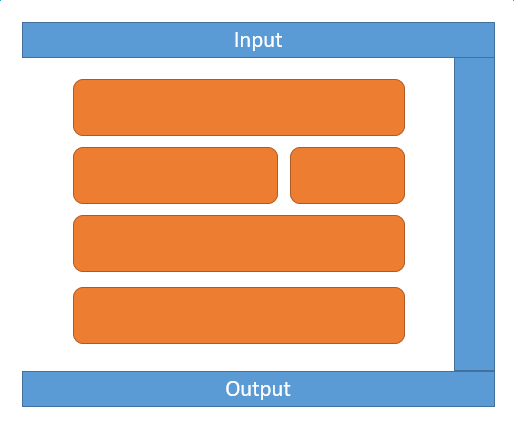

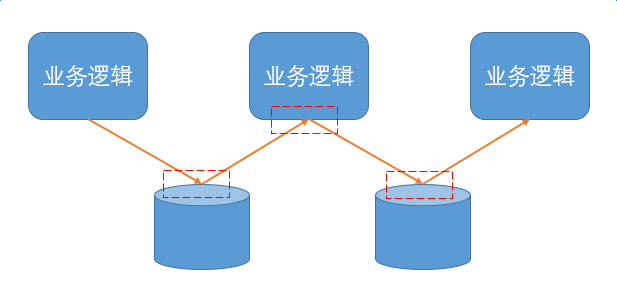

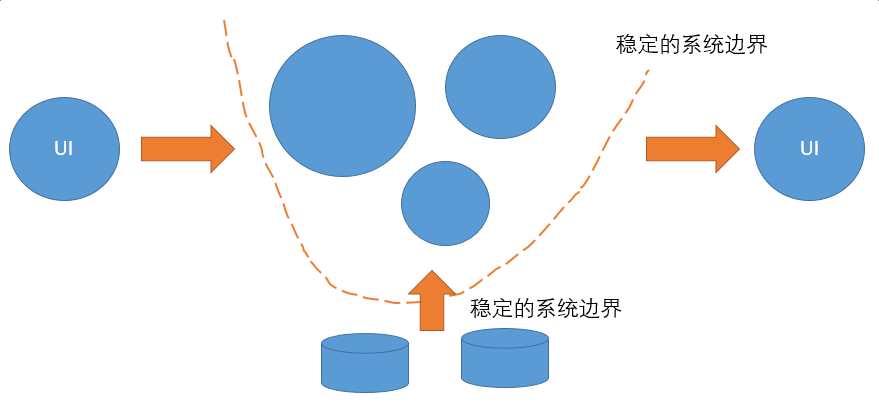

- 测试基于稳定的系统边界。向上,稳定边界是和界面的数据API接口。向下,稳定的边界是数据存储的表结构。中间的无状态的业务系统之间的调用,就当函数之间的调用来理解就好了。

- 测试的对象从一个语言一个进程内的函数,改成一个进程组。Mock不再是对函数的Mock,而是对网络调用的基于协议的Mock。

预期的工作流程是

捕捉一个http调用的全流程记录,记录其所有的输入输出和数据库交互

修改这个全流程记录,把新的需求和预期

在线上跑一下这个修改的全流程记录,发现不符合预期

修改代码,部署差异版本,这个版本不接正式流量

用差异版本重新跑一个全流程的记录,发现仍然不符合预期

修改代码里的bug,重新部署

用差异版本重新跑一遍,发现ok了

继续下一个测试

听起来很美好是吗?这和 TDD 并没有什么不同。只是把对一个函数的测试,改成了对一个http接口的测试。把线下的测试,改成在线的测试。从每次测试把数据库清空,改成了测试的副作用收集到特定存储里。

而我相信,建立一套中间件,使得任何技术现状,任何语言,任何框架的团队都可以享受TDD的红绿红绿的开发节奏,从而极大缩短修改代码到得到反馈的周期,这个收益是足够大的。不要以为你们写一个中间件可以百万QPS,可以节省xx台机器是很牛b的事情。对于公司的收益来说,需求迭代速度是衡量任何开发团队对公司价值最重要的指标,没有之一。既然迭代速度这么重要,为什么不能建立一套快速给开发者反馈,以提高迭代速度为目标的中间件呢?哪怕这个技术现在看起来就像深海钻井一样,是一个复杂的系统工程。

为什么 TDD 没有火起来?因为它太脱离现状了(测的是函数,而不是系统),太需要因材施教了(看看Mock框架有多少种吧)。如果把 TDD 从函数级别,升级到系统级别,反而可以极为可复用

- linux/windows/mac

- udp/tcp

- http/thrift/protobuf

- mysql/postgresql/redis

这些进程间的接口是可枚举的,可积累的。

以前需要专家在你使用的语言,框架,API上封装一层接口,才能愉快的TDD。可惜专家是很贵的,专家是很忙的。而且对于遗留地,乱七八糟的项目,这种封装层根本就建立不起来。

而改成系统级别的TDD,无论你现状是什么语言,写得是怎样乱七八糟。对外的网络接口始终是清晰地,始终是可统一化处理的。

另外一个额外的经济考量是,线下搭一套开发环境,并维护其稳定是需要额外支付的成本。而线上的系统支持多租户,往往是业务的必须。测试用户的测试数据,就是你的网站的一个特殊的用户而已。这种多租户的支持的成本是已经支付过一遍的。

愿,梦想成真。虽然今日的生活是如此苟且,不妨碍我们畅想诗与远方。

此文属于革命性中间件系列,前情提要 “解决业务代码里的分布式事务一致性问题 - 知乎专栏”