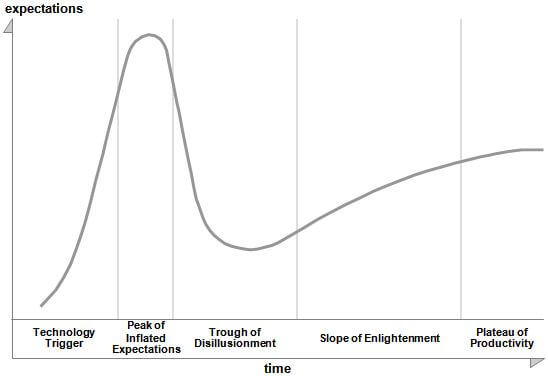

Elixir is a hot and trendy topic nowadays. Of the newer languages that show up periodically on Hacker News, I found that people were the most positive about it, even moreso than Rust. But of course, no language is ever going to be a silver bullet.

Elixir - at the peak of inflated expectations? (source)

So I compiled this list of reading notes, quotes, links and some personal thoughts about Elixir from using it to build some side projects, such as an app that finds stressed syllables or a collaborative text editor. The goal is to really understand Elixir to answer questions such as:

- What is it good at doing?

- In what way?

- Under what circumstances?

- What is it not good at doing?

- What are current pain points?

- What are the tradeoffs?

Since I have a decent compilers background, I’ll make use of that too to answer those questions.

I don’t intend this blog post to have a narrative, it’s more like my public research diary or a compilation of summaries. It doesn’t need to be read from top to bottom, though you can certainly skim through it and it should be pretty useful for getting a summary if you’re new to Elixir, or generating leads of things to read next. It’s quite long, but it’s a couple weeks worth of Elixir learning, after all.

See also the discussion on Hacker News of this blog post - it has a lot of great clarifications and information that I omitted!

What is Elixir?

Basic properties of the language include:

- Functional

- Strongly typed

- Dynamically typed

- Super cheap green threads

- Communicate via message passing

- Ruby-like syntax

Reasons for which people typically get excited include:

- Easy to learn

- Pragmatic

- Very easy to build concurrent programs and distributed systems with

- Lots of built-in features for building reliable systems/devops

- Can create upgradable systems with very high uptime

- Community is active, supportive and productive (good libraries/tooling)

Things it’s not so good at include:

- Raw compute performance (e.g. numeric)

- Optimizing memory usage

- Concurrency use cases requiring shared memory

- Interop with other languages

- Giving the most possible power to the programmer in abstraction capabilities

Relationship with Erlang

You’ll see me use Elixir and Erlang interchangeably throughout this document. That’s because Elixir is a language that runs on the BEAM VM, the same as Erlang. Kind of like how both Scala and Java run on the JVM. However, the two major changes are:

- Ruby-like syntax that is more accessible than Erlang’s Prolog-like syntax

- Macros for metaprogramming

There’s other things, but the point is that there’s very little change in the runtime of the language, so calling Erlang functions from Elixir or vice-versa is trivial and only occasionally needs some conversion boilerplate (e.g. non-unicode strings to unicode strings).

I do tend to use Erlang more often when referring to language and runtime implementation details, and Elixir more when referring to newer features or in the context of web development.

Do you need to know Erlang to learn Elixir? To some degree yes, some useful library functions have not been reimplemented in Elixir since the Erlang equivalent works just fine. But it’s often just a slightly syntax difference. There’s also useful Erlang libraries (e.g. I’ve used erlport). But in my experience, you can learn about Erlang as you go, it’s fine to ignore Erlang when starting with Elixir.

Some people might disagree.

“You can’t really get around learning Erlang. When you build applications with Elixir, you build applications that live on the Erlang ecosystem and runtime. With time, you will have to get to know Erlang, too, if you want to use the whole package efficiently. Also consider that there is a very high number of Erlang libraries available, all of which you can use from Elixir. If you jump into Elixir thinking “it lets you use Erlang without having to deal with its unfamiliar syntax”, you’re going to miss out on many of the good bits from the ecosystem.” - Hendrik Mans (source)

More on the difference between the two:

“I’d say Elixir is the sharper tool. It cuts better - and I don’t mean the syntax, but the macros - which can be a bad thing if you slice yourself by mistake. Erlang, with its small and hard to extend syntax, its libraries, frameworks, and conventions, is geared towards stability. Erlang is meant for creating reliable systems, which will be maintained for decades. Erlang is the most conservative (in the sense Steve Yegge’s post) of dynamic languages out there: it’s verbose, predictable, boring, consistent, reliable and focused solely on fault-tolerance (ie. long term stability).” - Klibert Piotr (source)

Why learn yet another new language?

“Erlang is not a programming language in the sense that other languages are. Erlang was not designed from the language in. Erlang (ERTS) is a runtime, and was designed from the runtime out, with Erlang being effectively a pure side-effect: the language that ended up being required to interact with the features of the ERTS runtime.” - deref (Levi Aul) (source)

This makes the sales pitch for Elixir quite unique compared to other languages. In my experience so far, Elixir is a nicely crafted and tasteful language (more than Erlang), but the language itself is less than 50% of the story. The real selling point is all about the runtime.

Implication: replicating runtime features of Erlang is far harder than replicating superficial features. Languages that have been considered flawed (e.g. Javascript, Java, Objective-C) have had improvements that have made them quite better (e.g. ES6/Typescript, Java 8/Kotlin, Swift). They’ve adopted adopting newer language features, often from functional languages (e.g. optionals). Sometimes they become good enough to deprecate competitors (e.g. CoffeeScript) that competed on just being “nicer”. I don’t expect that any extension of existing languages though will deprecate Elixir or Erlang because of how deep its benefits are embedded within the runtime.

Three key elements of Elixir

If I had to summarize Elixir, three of the most important aspects might be:

- Simple immutable data structures

- Actor-style message passing between isolated processes

- OTP library to build resilient systems via easy crash recovery (i.e. “let it crash philosophy”)

Which have a lot of implications individually, and when put together. It’s a combination of design elements (along with a few other things) that really make sense as a complete package.

Simple immutable data structures

The vast majority of the time, data in Elixir is represented using primitives (int, strings), lists, tuples, structs and maps (dictionaries). Elixir is not OOP, so no objects with methods. Rather, it takes the functional approach of a complete separation

between data and logic. So instead of calling obj.setField(value) → void you call setField(obj, value) → new object.

Actor-style message passing between processes

Processes don’t share memory, so the only means of communicating between processes is to send messages. Processes have a message queue (implemented in the BEAM VM).

(This is basically the actor model)

Message passing is at the root of everything in Elixir - Brian Cardarella, DockYard

Resilience via “let it crash”

The way of organizing Elixir code in processes makes it runs more like a distributed system than a single sequential program. As such, it makes sense to treat it as a distributed system and to focus more on handling crashes than trying to avoid them by handling every possible error case (either via exceptions or Go-style return values).

“Imagine a system with only one sequential process. If this process dies, we might be in deep trouble since no other process can help. For this reason, sequential languages have concentrated on the prevention of failure and an emphasis on defensive programming. In Erlang we have a large number of processes at our disposal, so the failure of any individual process is not so important. We usually write only a small amount of defensive code and instead concentrate on writing corrective code. We take measures to detect the errors and then correct them after they have occurred.” - Matthias Verraes (source)

Kinda like Chrome tabs actually, which if I remember was a significant innovation in making browsers work better.

That being said, where it makes sense, Elixir uses Go-style return values for representing errors, which works well with Railway-Oriented syntax.

More on why this approach makes sense later.

How they go together

By data decoupled from logic, you can send data across the wire without worrying about the code. If you had a class, it would be harder to send because you’d have to make sure the other side also had a class with the same field and methods.

“As a follow-up to that, why can’t we define types in a JSON API? We can define a type on either end, but everything is just going to be serialized to a string, sent over the wire, and then deserialized on the other end back into whatever type you’ve defined.

That’s an important detail when you consider that Elixir works using message passing. Elixir functions are set up so that they can transparently be called across processes, heaps, or even machines in a cluster. You might say you’re sending some fancy, contrived type that you’ve created, but underneath it all it’s just a collection of basic data types with a name attached to it.” - Barry Jones (source)

Elixir the language

Dynamic and strongly typed

It’s easy to see that Elixir is dynamic from a glance at the syntax. However, what’s not immediately apparent is that it is dynamic and strongly typed, a rare combination.

The definition of “strong vs weak typing” is not as well agreed-upon as “dynamic vs static”, but one way to think about it is that weakly typed systems will implicitly cast between types and allow types to interact (e.g. convert an int to a string

when doing "test" + 10). Strongly typed systems don’t allow types to change and interact implicitly.

Elixir/Erlang is in this relatively rare category. You don’t ever declare types, but the language does very little magic for you. There’s also no operator overloading. For example, ("Hello," + " World!") won’t work, there’s a separate

operator ("Hello," <> " World!").

Addendum (08/25/2017): Python and Ruby are technically strongly typed, but overloaded operators combined with many many ways to override basic language behavior make them closer to weakly typed for the purpose of this discussion.

Resources: https://blog.codeship.com/understanding-elixir-types/ http://stenmans.org/happi_blog/?p=176

It’s also the least dynamic language among dynamic languages that I’ve tried so far (Python, Ruby, Javascript, Racket). There’s very little room to do any magic at runtime. There is a Lisp-style macro system that operates at compile-time (which I haven’t used yet).

In practice: In my coding experience so far, I’ve felt safer about writing code without types than I do in other languages. In some way, a lack of feature is a feature.

Question: Is writing libraries difficult as result of these lack of features?

Question: How does having a macro system compare with runtime dynamism?

Optional typing

Elixir allows adding type annotation (I think only for functions) via Typespecs and static code analysis via Dialyzer.

Dialyzer can run without any Typespecs, by using a type inference technique called success typing. It will, however, check the inferred type against the optional types, which tells you if the function does something different than what you think it does.

I think that the simplicity of Elixir types allow for a tool like Dialyzer to work.

In practice: While Dialyzer is extremely simple to setup and run, I found that it gave me warnings on relatively standard Phoenix code that I do not understand (the fact that it’s an Erlang tool and outputs errors in Erlang syntax doesn’t help). I found Typescript to be more straightforward to use. Having Typespecs is nice and is a form of self-documenting code and found myself wanting to use it more after trying it out on one file, though the false positives of Dialyzer make it a little harder to use.

Consequences of simplicity

“What Erlang is not really suited for is where you need multiple levels of abstraction, such as when implementing complex business logic. You would think that the functional nature of the language lends itself to that, but then you quickly realize that because the primary concern of an Erlang engineer is to keep the system alive, and for that reason you must be able to reason and follow the code as it is running on the system, all kinds of abstractions are very much discouraged and considered bad practice (look up “parameterized modules” for an example of a feature that was almost added to the language but was discarded in the end).” - haspok (source)

While Elixir has better support for abstraction (namely via macros), the statement still holds and this changes the sales pitch for Elixir quite a bit. People often associate functional language with abstraction, but the amount of abstraction that you would write in Elixir is less than most non-functional languages. Haspok follows up with.

“I think that from this perspective Erlang and Go are actually very similar - both prefer simplicity over abstractions.”

Being more systems-focused, it naturally means that Elixir is less accessible to people with minimal programming background (it’s very accessible if you have prior programming experience). Python and Ruby’s magic, for all their flaws, have benefits for non-experts such a scientists who have limited spare capacity to learn coding. (I hesitate to also add “or such as web developers” which may offend some people, but it’s totally fair for non-programmers that want to make a website to start with frameworks like Rails that have DSL-like properties. For users of a language that don’t have the time to either understand existing magic or create magic themselves, the next best thing is to give them tools that do lots of magic and work most of the time given a bit of trial-and-error).

“There are only a handful of languages which are truly doing concurrency these days. One of them is Go with its goroutines and channels, and this is a large part of its appeal. […] On the other hand, if you actually listen to a lot of Go users, that is the primary selling point: the language is small, you can understand it in a day […]” - Aaron Lebo (source)

Concurrency, parallelism and distributed systems

“…each process can contain its own state - in a way, processes in Elixir are like objects in an object-oriented system (except they’re more self-contained)” - Dave Thomas in Programming Elixir 1.3

Everything I’ve read on Elixir emphasizes the ease of doing concurrency in the language.

“Doing concurrency in Erlang or Elixir versus other languages is a bit like doing branches in Git vs Subversion. In subversion it was very complicated to do - and I never did it. In Git it is a lot easier and I do it all the time.” - Lau Taarnskov (source)

Three primitives to spawn processes and send/receive messages are spawn, send and receive.

Makes sense.

Parallelism

Since Elixir processes have isolated memory only communicate via message-passing, the BEAM VM is free to execute these processes on any core of the machine it feels like and it will just work.

However…

“Erlang was built for concurrency, parallelism is a side effect and a just nice-to-have.” - Jaseem Abid, has worked with Erlang in production

The distinction here is that Elixir/Erlang emphasizes ease of writing concurrent code, not performance. It’s nice to have a trivial implementation of parallel_map that runs on all four cores of your machines, but you could probably get a 4x speedup just by rewriting the code in C++.

Emphasizing concurrency has a lot of implications on programmer productivity. Consider how IO in Elixir is implemented as a process. So while IO.puts "Hello, World" blocks on the caller, it doesn’t block the thread (because while it’s

waiting for an ack message from the IO process, other threads run). No callback code required. Now imagine this model all over your program.

“I really love Ruby/Rails, but what led me to Elixir in the first place was constantly dealing with lack of concurrency in Rails and being unable to do anything like websockets in a sane way. For example, in Rails we can’t really block in the controller without killing throughput, so we go to great lengths to background everything. This makes simple problems like “Make a remote API request through a controller” way harder since we now have to throw it in a worker queue, then poll from the client on the status of the job, then finally return the result. In Elixir/Phoenix, we can block in controllers without a blip on throughput, do our work, and return the response.” - Chris McCord (source)

Resources: https://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/io-and-the-file-system.html

Distributed systems

“Premature optimization is costly. Rewrites caused by quick and dirty work are as well. Thanks to message passing and processes of Erlang there is actually a very nice path for scaling from small to large while reducing waste:

- Design your code around processes

- Separate these processes into OTP apps

- When an OTP app gets too much load, move it to its own node on better hardware” - Adrian Philipp (source)

The way Elixir code is organized is via Modules (essentially namespaces). Some modules might just be a collection of utility functions (e.g. 3D vector operations). Others will encompass functionality similar to a class (e.g. User module, Document module, Cache module, etc). In Elixir, it’s really easy to spawn processes and an idiomatic pattern is to turn a module into a process is a GenServer.

Example:

defmodule MyProject.User do

defstruct username: ""

def start_link(username) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, %User{username: username}, name: __MODULE__)

end

def get_name(pid) do

GenServer.call(pid, :get_name)

end

def set_name(pid, newname) do

GenServer.call(pid, {:set_name, newname})

end

def handle_call({:set_name, newname}, from, state) do

...

...

While there is a bit of boilerplate, it’s quite simple overall. start_link is the equivalent of a constructor, and functions in the module are just like methods that happen to send messages to the process instead of mutating state directly.

The instance/object/process on which the method is called is passed explicitly, much like self in Python.

I initially thought Elixir could automatically assign processes to different machines in the same way it can automatically assign processes to different cores. This is not true, but it is the case that spawning a process on a different machine is as simple as passing the name of the machine to GenServer.start_link. Since processes communicate via message passing which is handled by the VM, nothing else in the program needs to be changed. What makes writing distributed systems simple is, in other words, that the API works

irrespective to where the process is physically located.

Microservices

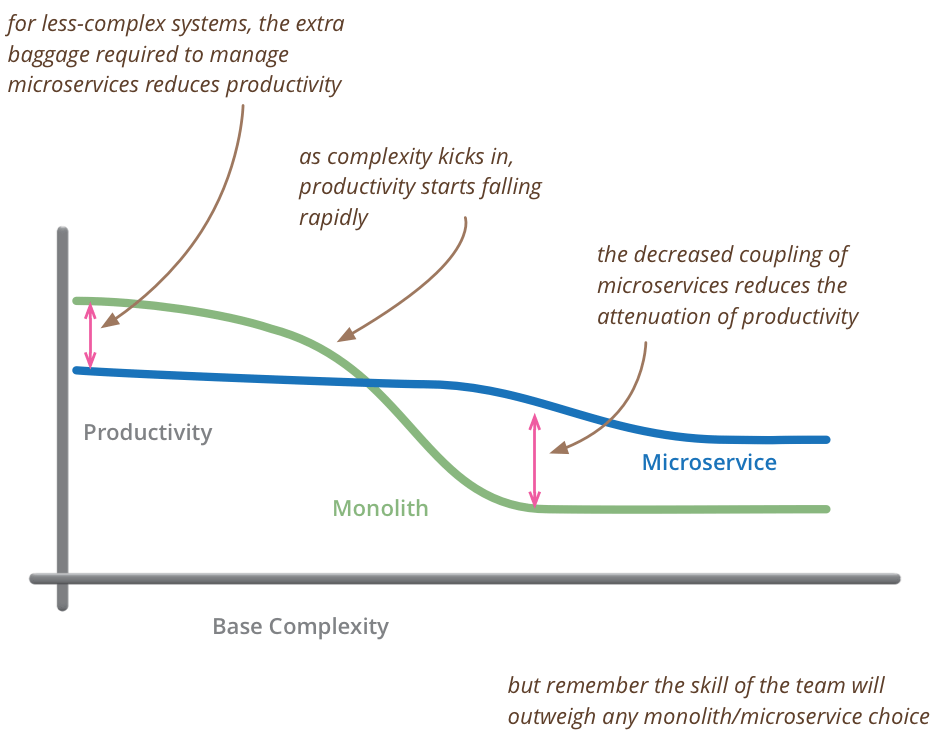

The tradeoffs of building a monolith v.s. microservices is something like this:

(source)

However, since the natural design pattern in Elixir is to organize code in isolated processes, Elixir code is written as microservices by default without the extra baggage that comes with microservices.

This works in theory. In my very limited experience writing a web app that runs on two machines, this seems to also work in practice.

Elixir also comes with a feature (or rather tooling?) called Umbrella projects which splits apps.

“For me, Umbrellas give us the microservice architecture” - Chris McCord (source)

In that same video, he has a flowchart for whether to use Umbrella projects (microservices).

Does my context manage it’s own storage?

→ Yes: Consider Umbrella

→ No: Keep in same app

Accidental v.s. essential complexity

As mentioned in the intro, Elixir is no silver bullet. While hyped for concurrency, distributed systems is hard and It doesn’t solve any distributed system problems for you. For example, in a master-replica setup with a transaction log, it’s up to the system designer to deal with cases where the replicas are lagging behind - Elixir can’t deal with that, since it’s essential complexity.

Rather, what Elixir achieves is get rid of all the accidental complexity around distributed systems by making sending messages so easy (e.g. serializing data for you).

“People tend to forget that scalability is not a binary property. You always scale up to some users, up to some architecture, up to some amount of nodes. There is no system that will scale to infinity without requiring developer intervention once business needs and application patterns start to settle in.” - Jose Valim (source)

Fully meshed networks

Making clusters of nodes is really easy.

However, the network is fully meshed (that’s what allows processes to talk to each other and allow the programmer not to worry about where they are). This has limitations.

Distributed Erlang/Elixir has known limitations. For example, the network is fully meshed, which gives you about 60 to 200 nodes in a cluster. Or don’t send large data over distribution, as that delays the other messages, etc. Some of those are easily solvable. For example, you can rely on your orchestration tools to break your clusters in groups. Or you can setup an out of band tcp/udp socket for large data. Others may be more complex. The important question, however, is how far you can go without having to tweak, and, once you reach those roadblocks, how well you can address them. In many platforms, writing a distributed system is a no-no or, at best, they require you to assemble and tweak from day one. In this case, the ability to start with Erlang/Elixir and tweak as you grow is a feature. - Jose Valim (source)

Anecdote (warning: lots of guesswork): How many nodes do you need? If I remember correctly, Airbnb’s business front-end (the part that’s a Rails monolith) uses 300-600 machines. So I think 60-200 Elixir nodes would be enough to power a good portion of Airbnb, as you need far fewer servers to serve the equivalent amount of traffic in Phoenix than Rails.

Question: Does the amount of messages sent by the VM scale quadratically in practice? Why/what kind of messages are sent?

Question: What do people do when they hit the limits of a fully-meshed network?

Resources: https://blog.discordapp.com/scaling-elixir-f9b8e1e7c29b http://kanatohodets.github.io/2016/05/22/elixirconfeu-2016-scaling-distributed-erlang.html

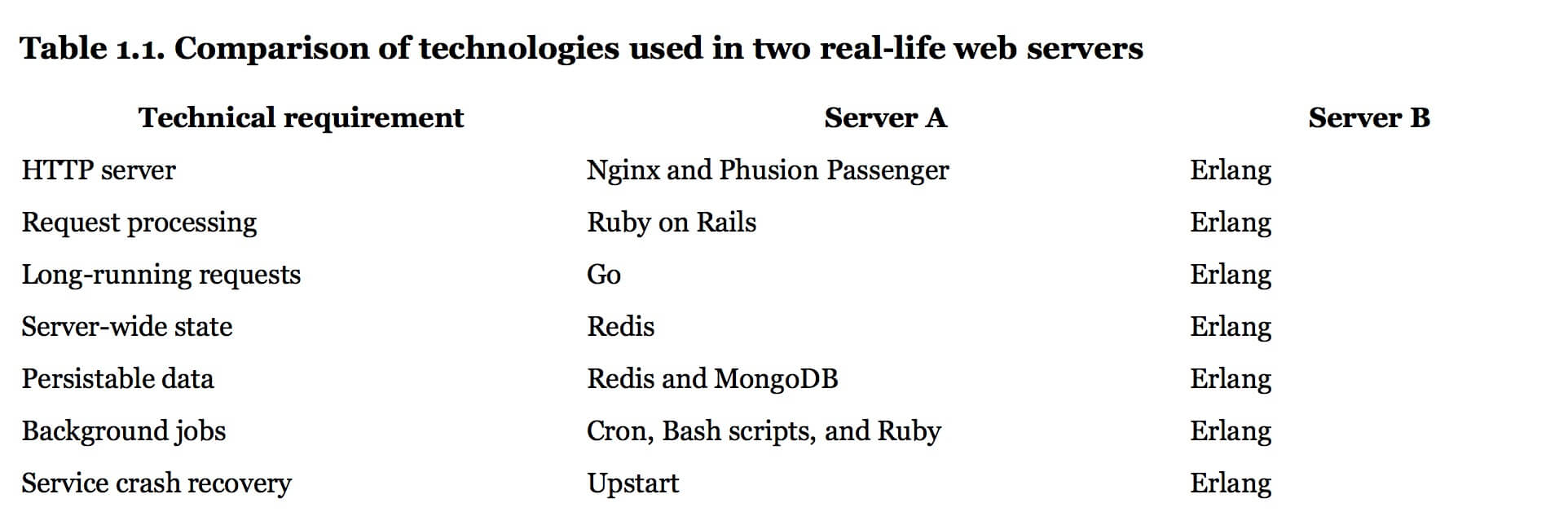

Interop with other systems

Things in Erlangworld work best when everything is written in Elixir/Erlang and works together.

(source)

Elsewhere in this document, I discuss how calling other languages from Elixir needs to be done carefully to avoid messing up the VM’s scheduler. It’s also common for languages that are very opinionated to interface badly with other languages. However, in a distributed system this should be less of a problem since everything communicates via message passing anyway. This may, however, affect the ability to use OTP’s capabilities like supervision trees.

Question: How does one design supervision trees when non-Elixir components are involved?

GenStage

Elixir comes built-in with GenStage, a producer-consumer work pipeline. With GenStage flow, it looks like you can build data pipelines with Spark-style functional operations. Consumer-producer pipelines should definitely be an important part of a distributed system, and one that is easy to get wrong because you want to handle tricky edge cases like doing backpressure properly. That being said, I’m not experienced enough with writing large systems that handle large amounts of data to evaluate GenStage at this point.

Question: How good is GenStage from a technical perspective? Question: When do you use GenStage v.s. regular message passing? Question: What are good uses cases of GenStage?

Resources: https://elixirschool.com/en/lessons/advanced/gen-stage/ https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=13161505 https://github.com/elixir-lang/flow

Discord case study

Discord wrote a blog post about using Elixir at scale, which then prompted a good discussion on scaling on HN: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=14748028

Elixir implementation

Compilation

“Elixir always compiles and always executes source code.” - Xavier Noria (source)

This may both be surprising and totally not surprising. It’s surprising because we often tend associate static language with compilation, and dynamic language with, well, not compilation. On the other hand, it is not surprising because Python and Ruby are also compiled to bytecode.

Compilation means a little more for Elixir than it does for Python or Ruby because it includes a macro expansion phase that transforms the AST.

Question: What are the implications of being compiled? What does the compiler do?

One consequence I am aware of is that it allows Elixir to have very fast implementations of features like pattern matching or routing because it can generate code paths for those complicated language features.

“The router compiles down to cat-quick pattern matching. You won’t have to spend days on performance tuning before you even leave the routing layer.” - Chris McCord in Programming Phoenix

Elixir also seem to compile quite fast. The first compilation needs to compile all the dependencies, including Phoenix (a big framework) and all its dependencies. This seems to take about a minute or two.

Question: How fast does Elixir compile, and how does it compared to other languages?

Compute performance

To the best of my knowledge, Elixir is considered fast for a dynamic language (e.g. versus Python, Ruby) in terms of compute performance, which makes sense, since it is far less dynamic therefore more optimizable. On the other hand, it’s not considered to be that fast compared to static languages. Elixir is not considered to be well-suited for compute tasks.

Question: How fast is Elixir exactly? Find convincing benchmarks.

No JIT

Unfortunately, Elixir does not have a production-ready JIT like V8 for Javascript (BEAMJIT not withstanding). The BEAM VM, while a magnificent piece of engineering, is optimized for concurrency, not compute performance.

On the other hand, I’m not quite sure what kind of JIT optimizations would be useful for Elixir. For example, Elixir doesn’t have a prototype system like Javascript which means hidden maps and inline caches are less applicable. By being strongly typed, it also doesn’t need to do a ton of runtime checks for every add operation, which inline caching or other compilation approaches are meant to solve.

Concurrency performance

Elixir processes are actually green threads, which are user-space managed threads that are much cheaper than operating system (kernel-side) thread/processes. Rather than the OS preempting the thread via a hardware interrupt, green threads will yield themselves to allow other threads to run (this usually requires language-level support to add those yield instructions).

A super good tutorial on how green threads are implemented that I really enjoyed is C9x’s. It took me 1-2h of sitting down and reading carefully, it’s certainly not trivial to understand, but the core idea is quite simple. Simple enough that I could reasonable give an overview in a 5 minute presentation at Recurse Center.

Other languages that use green threads include Go (Goroutines), Haskell, OCaml. However, Erlang processes are unique in it’s kind.

Compared with OS threads

Operating system threads are generally larger. It can be a bit hard to figure out exactly how big they are (since they may commit virtual memory without backing with physical memory until needed) but they can still start >100kb.

Erlang processes conservatively start at less than 1kb to support use cases involving creating millions of processes. Green threads don’t need to go into kernel mode, which saves some overhead switching between threads.

Starting a million processes on the operating system could prevent essential operating system functions from executing. But since all the green threads only run on a few OS processes, it’s safe to create a lot of them.

Resource: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/11433880/size-of-a-process-thread-in-linux http://erlang.org/doc/efficiency_guide/processes.html

Compared with Go’s green threads

Go’s goroutines are neither memory-isolated nor are they guaranteed to yield after a certain amount of time. Certain types of library operations in Go (e.g. syscalls) will automatically yield the thread, but there are cases where a long-running computation could prevent yielding.

Reference: http://www.sarathlakshman.com/2016/06/15/pitfall-of-golang-scheduler

Compared with Haskell’s green threads

Haskell’s green threads are a little bit more similar to Erlang’s green threads in that the language is also functional and data is immutable. However, there is only one heap for all the green threads, rather than one heap for each green thread/process. The downsides of this are worse garbage collection and lack of ability to do some of the nice things Erlang can do like easily spawn processes on other machines, supervisors, etc.

Reference: https://www.quora.com/How-are-Erlang-processes-better-isolated-than-Haskell-green-threads-or-Akka-Actors https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=11451510

On preemption

“So how does Erlang ensure that processes don’t hog a core forever, given that you could theoretically just write a loop that spins forever? Well, in Erlang, you can’t write a loop. Instead of loops, you have tail-calls with explicit accumulators, ala Lisp. Not because they make Erlang a better language to write in. Not at all. Instead, because they allow for the operational/architectural decision of reduction-scheduling. Without loops in the language, every function body will execute for only a finite amount of time before hitting one of those call/return instructions, and thus activating the reduction-checker.”

“Erlang does a different thing called “reduction-counting”: the active process in a scheduler-thread gets a budget of virtual CPU cycles (reductions/”reds”), tracked in a VM register, and part of the implementation of each op in the VM’s ISA is to reduce that reduction-count by an amount corresponding to the estimated time-cost of the op. Then, the implementation of the call and ret ops in the ISA both check the reduction-counter, and sleep the process (scheduling it to resume at the new call-site) if it has expended all its reds. (If you’re wondering, this works to achieve soft-realtime guarantees because, in Erlang, as in Prolog, loops are implemented in terms of recursive tail-calls. So any O(N) function is guaranteed to hit a call or ret op after O(1) time.)”

One consequence of pre-empting processes this way is that if Elixir calls into another language, the BEAM VM won’t be able to stop execution while code in that other language is running. This means that foreign interface calls from Elixir need to be done more carefully than in other languages as it could break the guarantees of the language. This is a somewhat important downside of the language, since Elixir is a dynamic language and it’s typical to write optimized code for things that really need it like matrix multiplications (e.g. NumPy). The best practice is to spawn a process in that other language and communicate with it through message passing (this is what the Erlport library does).

Memory performance

As a dynamic language, Elixir needs to store information about times at runtime, which induces overhead.

Ryan Schmukler wrote a medium article about loading a 350MB CSV into memory which took 2 GB, a 5.5x increase.

Question: How does Elixir memory usage compare with Python and Ruby?

Also, since processes have isolated heaps, sharing data between processes can only be done via message passing (i.e. copying). While there are some optimizations in regards to the handling of large binaries, use-cases that require shared memory are going to be fundamentally less performant.

On garbage collection

The fact that each process has its own memory and each process is small means that the runtime can do many mini garbage collections on each process. This reduces tail latency (frequency of latency spikes).

Erlang’s garbage collector is a copying semi-space generational collector, which have compaction properties beneficial for cache performance. Since data is immutable, the generational collector needs to do less work:

“Fortunately, this comes naturally for Erlang because the terms are immutable and thus there can be no pointers modified on the old heap to point to the young heap.” - Lukas Larsson

Exception: there’s a separate heap for large binaries, which is apparently not that good.

“It’s a well known fact that Erlang VM’s generational GC does not do well when trying to garbage collect non-heap binaries.” - Panagiotis Papadomitsos (source)

Reference: http://prog21.dadgum.com/16.html https://www.erlang-solutions.com/blog/erlang-19-0-garbage-collector.html http://blog.bugsense.com/post/74179424069/erlang-binary-garbage-collection-a-lovehate

Question: Any good benchmarks that quantify how fast garbage collection in Elixir is?

Tooling

I don’t have much to say here, but Elixir tooling seems pretty good in my experience. Things work as expected and setup is not particularly complicated.

Elixir. Why? Because it has tooling that is up to the high standards you’re used to using in Ruby and Rails. It has a great ecosystem, package manager, and build tooling. The documentation is fantastic and filled with examples. - jfaucett ( source)

It comes with Rails-like tool for generating boilerplate and migrating databases. It has integration with Vim, Sublime, Emacs, VSCode (which I’ve defaulted to using when my frontend is in Typescript).

For a new language, I think the state of tooling is fairly impressive (except deployment - see section on deployment). Lots of functional languages that could otherwise be quite useful suffer a lot on the tooling department.

Question: How does Elixir tooling compare to popular languages in more advanced (e.g. industrial?) use cases?

Resources: http://blog.plataformatec.com.br/2016/04/debugging-techniques-in-elixir-lang/

The “REPL”

One tooling that Elixir has is worth mentioning. It comes with a REPL, like all modern languages. But it’s not really a REPL. As you’d expect from how things are done in Erlang, the REPL is more like a shell from which you can communicate with existing processes.

This still gives you all the functionality of a normal REPL, but it also allows you to attach to an Erlang VM with running processes and communicate with them without interrupting them. That’s pretty cool.

This gives Elixir really powerful introspection tools.

Resources: http://ferd.ca/repl-a-bit-more-and-less-than-that.html http://erlang.org/pipermail/erlang-questions/2014-November/081570.html

Phoenix

Relationship with Rails

Elixir being inspired by Ruby syntax, and Phoenix being inspired by the Rails way of doing things, there’s a lot of parallels. Clearly Elixir/Phoenix were designed with the intent of being better than Ruby/Rails. On the other hand, I don’t find that the Elixir community disses Rails the way other language communities often do. While I personally don’t like the experience of using Rails, Rails was an innovation that made web development a lot more productive for a lot of people. Elixir/Phoenix seems to have more respect for Ruby/Rails and therefore learn from the things it did do well.

“Sure. So let me start by saying I have worked full-time in Ruby/Rails at a Rails shop for the last four years. Phoenix is derived from that experience, and we borrow some great ideas from Rails.” - Chris McCord (source)

Interesting points

- Jose Valim (creator of Elixir) used to be a Rails core team member

- Dave Thomas (author of Programming Elixir 1.3) wrote books on Ruby and ROR

Question: Are there other high-profile Rails people that switched to Phoenix?

Rails to Phoenix talk notes

These are some key points I noted down from Brian Cardarella’s talk. https://youtu.be/OxhTQdcieQE

Performance

- Common to see sub-millisecond response times

- Bleacher Report case study

- Switched from Rails to Phoenix, served the same traffic with 10x (!) fewer servers

- Smaller latency spikes

- No longer need caching

In what way performance matters (and this is important)

- Past a certain point, performance doesn’t necessarily matter (or isn’t the most important thing)

- Does the user notice enough?

- Does the boss care enough to let you use a new framework?

- “As Rails developers, we are told: we should make a sacrifice of performance for productivity”

- Rails operates at the boundary of acceptable performance, so it’s constantly necessary to optimize, which takes time

- The value Phoenix has in being fast is that it operates so far above the boundary of acceptable performance that you don’t need to spend time optimizing (almost)

- e.g. don’t need to do caching anymore, and caching invalidation is hard and kind of an accidental complexity

“We keep getting reports of Phoenix without caching being faster than other solutions with caching. Good perf lets you focus on what matters!” - Chris McCord (source)

Question: Are there other documented case studies of other companies achieving similar productivity gains for similar reasons?

Happiness

Brian’s main thesis you build something in half the time for half the cost. Business people are happy. The Ruby of today is nice, the one of last year not so much. Phoenix solved that for him. Developers are happy.

“Elixir & Phoenix optimize for long-term developer happiness”

Easy to learn for Rails people

“But Phoenix is so similar on its face that if you are already familiar with an MVC framework like Rails, then you’re going to have a much easier time transitioning to it”

Anecdotally, I can attest that Phoenix feels very similar to Rails, except that I liked it this time.

Resources: http://www.techworld.com/apps-wearables/how-elixir-helped-bleacher-report-handle-8x-more-traffic-3653957/ https://pragtob.wordpress.com/2017/07/26/choosing-elixir-for-the-code-not-the-performance/

Also, elsewhere:

“So, we like Elixir and have seen some pretty big wins with it. The system that manages rate limits for both the Pinterest API and Ads API is built in Elixir. Its 50 percent response time is around 500 microseconds with a 90 percent response time of 800 microseconds. Yes, microseconds.” - Steve Cohen, Pinterest (source)

Ecto & Databases

Ecto is somewhat analogous to Rails ActiveRecord and can be backed by Postgres, MySQL or Mnesia. I’ve only used it a little bit but it does seem to have a different philosophy than ActiveRecord.

“Ecto is likely going to be a little different from many of the persistence layers you’ve used before. If you want Ecto to get something, you have to explicitly ask for it. This feature will probably seem a little tedious to you at first, but it’s the only way to guarantee that you application has predictable performance when the amount of data grows.” - Chris McCord in Programming Phoenix

It won’t do preloads unless you ask it to. In general, it does less magic, which is representative of Phoenix as a whole. I like this because I’ve argued before that people mistakenly emphasize code readability when the important criteria should be understandability. That is, do you understand not only what the code wants to do, but actually does?

Question: How good is Ecto in large production systems?

Question: How does Ecto compare on other criteria, such as performance?

Resources: https://www.amberbit.com/blog/2016/2/24/how-elixirs-ecto-differs-from-rubys-activerecord/

Websockets and channels

I had heard Phoenix was good at Websockets, so I built a collaborative text editor since text editors are a high-interaction application that is a good use case for web sockets. The websockets part was…easy and I ended up spending most of my time writing Typescript. Which is the point of “being good at Websockets” I guess.

“It looks simpler because for the programmer it is simpler. Since Elixir can scale to millions of simultaneous processes that manage millions of concurrent connections, you don’t have to resort to request/response to make things easy to scale or even manage. […] This is why this chapter [the chapter on Websockets/channels] is shorter than the entire request/response section of the book and it’s also why Phoenix is such a big deal.” - Chris McCord in Programming Phoenix

I think green threads allow each connection to be its own individual process. And being Erlang’s memory-isolated green threads, those processes can be trivially distributed to multiple machines.

”- Phoenix Channels is a higher-level abstraction over raw WS. We spawn isolated, concurrent “channels” on the underlying WebSocket connection. We monitor these channels so that clients can detect errors and recover automatically without dropping the entire connection. This contributes to overhead in both memory and throughput, which should be highlighted with how Phoenix faired in the runs.

- Phoenix channels runs on a distributed pubsub system. None of the other contestants had a distribution story, so their broadcasts are only node-local implementations, where ours is distributed out of the box Phoenix faired quite well in these runs, considering we are comparing a robust feature set vs raw ws/pubsub implementations.” - Chris McCord (source)

I don’t have much to say other than using channel worked as I expected it to, but that was also my first time writing a Websocket application. Rails can’t reasonably create a process for every connection and/or channel/room. It’s also built to be stateless. So my understanding is that to support data that persists within a connection, you need to setup a Redis cluster to use ActionCable. Which is why it also tooks so long for Rails to support Websockets.

“You don’t have to work so hard to keep track of the conversation by using cookies, databases, or the like. Each call to a channel simply picks up where the last one left off. This approach only works if your foundation guarantees true isolation and concurrency.” - Chris McCord in Programming Phoenix

Question: Is my understanding correct?

Question: How does Phoenix’s support for Websockets compare with Node.js’ support for Websockets?

Question: Under what situations is Phoenix’s distributed Websocket implementation necessary, and when is it overkill?

Resources: https://blog.heroku.com/real_time_rails_implementing_websockets_in_rails_5_with_action_cable https://hashrocket.com/blog/posts/websocket-shootout https://dockyard.com/blog/2016/08/09/phoenix-channels-vs-rails-action-cable?updated http://phoenixframework.org/blog/the-road-to-2-million-websocket-connections

Deployment in Elixir & Phoenix

As of now, deploying things in Elixir is both good and terrible.

The good: Hot code swap allows you to change code at runtime with zero downtime, without even breaking WebSocket connections (!)

The bad: Tooling and best practices around Elixir are still immature and don’t reuse a lot of recent devops best practices.

Hot swapping

Hot code swapping means you can change code while it’s running. What makes this possible is how Elixir code is organized around GenServers (processes) and the amount of code that handles each individual message is generally quite small. So to change

the code, all one needs to do is to do it in-between messages and provide a function code_change(from_version, state, extra) to migrate to the new state. That’s it!

“Imagine ‘hot reloading’ as adding new bubbles next to old ones before they pop.” - Barry Jones (source)

HTTP servers already do the first part (wait until requests have finished) but they don’t have the state migration part, which matters for stateful connections like websockets. I know very little of devops but I had a hard time finding information about zero-downtime deployment when you have websockets. I found a tutorial that had a complex (to my eyes) solution but basically said:

“There is no such thing as pure websocket zero-downtime deployments. I’m sorry.” - Dan Jenkins (source)

I think doing hot code swaps on live Websocket connections should be doable, but…

Question: Is there any blog post/walkthrough of someone doing it to get a sense of the amount of complexity involved? (If not maybe I should write one)

Note that while code_change looks simple, it would probably be quite hard to implement if processes did have shared memory. In Elixir/Erlang, all the state of one process is in a single data structure (similar ideas in front-end allow

features like time-travelling debuggers).

Immature deployment tooling and best practices

Notes from “Real World Elixir Deployment” by Peter Gamache (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H686MDn4Lo8)

- Deployment is gonna hurt a little

- Erlang is good at “traditional” long-lived servers (as opposed to the more modern approach where servers “poof in and out of existence”

- Most modern devops tools like Docker seem to me like they’re addressing the “poof in and out” use case

- Best tools right now is edeliver

- My personal opinion: edeliver config is some ugly bash script, I wish we had better

- A gotcha: handling thousands of connections/processes is not trivial, ulimit puts a lower limit on the number of connections than Erlang can handle

Erlang and Elixir deployment shouldn’t look like less-powerful platform’s. If you want to take advantage of the full platform, you’re going to have to leave some of the current best practice in devops aside for now.

Also: it’s hard to use Elixir with services like Heroku because your instances won’t find each other by default (the way they’re supposed to).

Personal experience: it took me a day to figure out how to configure my Phoenix app to run on two servers and talk with each other. My “deployment” is some crappy hand-written bash script. This is probably more time than it should take. Then later

I had a problem where I couldn’t figure out how to migrate the database because my migrate script to use with mix ecto.migrate didn’t come with the bundled executable.

But on the bright side:

- Elixir is doing better than Erlang in terms of administration and maintenance

- Very easy to scale up to dozens of nodes

Question: How do Pinterest and Discord handle deployment? (The biggest Elixir users I’m aware of).

Devops, OTP and reliable systems

As of now I don’t have a whole lot of experience with either OTP beyond very basic uses, or devops as a whole. So I don’t have a great sense of what is considered “important” in devops world, or what the “real” difficulties are.

The concept of OTP is certainly interesting. In particular, you can attach supervisors to processes that will restart them if they crash. Then, you can make hierarchies of supervisors, and have different supervision strategies to handle crashes (“crash processes spawned later and restart all at once”, “crash all siblings”, etc).

One nice thing about this is that devops is built into the language, something that would otherwise be tedious to do on your own. Furthermore, OTP can solve a large range of problems and it’s the One True Way of writing things in Elixir. That means there’s tons of battlefield experience and learning resources on building resilient systems with OTP, from years of Erlang experience.

Think of OTP behaviors as design patterns for processes. These behaviours emerged from battle-tested production code, and have been refined continuously ever since. Using OTP behaviors in your code helps you by providing you the generic pieces of your code for free, leaving you to implement the specific pieces of business logic. - Benjamin Tan Wei Hao in the Little Elixir & OTP Guidebook

My personal experiences:

- Having a One True Way of doing things eases the learning curve considerably

- It’s nice to have known design patterns that are part of the language, which collapses the two steps of “figure out what you need to do conceptually” and “figure out how to implement it in your language”

- Having these nice building blocks has made me interested in devops problems which has not happened previously, probably because I perceived it as tedious work

- I’ve had a few experiences at this point where one technology (e.g. Elm) was much better at teaching you how to think in certain patterns (e.g. Reactive Programming) than others (e.g. React) because all the mist has been blown away and the view is super clear. I suspect learning Elixir/Erlang can make a programmer much better at devops by teaching clear patterns of thought.

“OTP doesn’t do any design for you, it gives you building blocks to assemble something that’s going to be fault-tolerant” - Fred Hebert, author of Learn You Some Erlang for Great Good! in an interview

To read later: The Little Elixir & OTP Guidebook Erlang in Anger Designing for Scalability with Erlang/OTP

Why restarting processes is a good idea

While the idea of restarting processes sounds cool, it’s not clear how well it works in practice. Couldn’t it just run into the same crash?

“The reason restarting works is due to the nature of bugs encountered in production systems.” - Fred Hebert (source)

From the above article, there’s different kinds of bugs. Most bugs are errors in your code that affect core features. They’re bad, and restarting won’t fix them. But most should be repeatable in development and hence will get detected and fixed reasonably quickly. The really hard ones are the Heisenbugs which by definition are difficult to reproduce, and they’re difficult to reproduce because they require specific conditions of what the state looks like. Restarting gets the state into a fresh state that behaves as we expect. If they got into a restart loop, then they’d probably be easily reproducible, therefore easy to fix.

In summary:

“Restarting a process is about bringing it back to a stable, known state.” - Fred Hebert (source)

This is also key in understanding to how to use supervisors correctly. If the process initialization logic can fail (e.g. trying to setup a network connection), restarting won’t get you to a stable state.

Testing

I need to look into this more, but it seems like Erlang makes it reasonable to model the execution of your entire system as a FSM to be used for property testing, enabling system-wide fuzzy integration tests. If this works well in practice, it could be a significant paradigm shift.

OTP in Elixir v.s. Erlang

Using OTP is largely the same in Elixir or Erlang. One difference, however, is that it’s easier to put off learning OTP for a while with Elixir (especially with frameworks like Phoenix) whereas Erlang puts it in your face right from the beginning. This has pros and cons. It makes the language more accessible since OTP is when it starts to become more conceptually difficult, but having to think about OTP really makes you think about building reliable systems.

Elixir community

This has nothing to do with the language itself, but the community around it is quite important. Different languages attract different crowds, which have different priorities. Ignoring this fact leads to swimming against the current.

Employability

Elixir is a new language and as with all new languages, it might easily take another decade for it to become mainstream. That being said, a there’s a useful GitHub repo that lists companies currently using Elixir: https://github.com/doomspork/elixir-companies

There seems to be ~200 companies in that list, which is not bad though of course nothing compared to the thousands that use Python, Java, Javascript, Ruby, etc.

Point of comparison: over 500-600 companies that use Go, around ~100 companies that use Rust. Go can reasonably be called mainstream within tech nowadays (not within IT as a whole, but sufficient for employment purposes). So relatively speaking, Elixir isn’t that far behind.

There are also more companies using Erlang. Some high-profile software like RabbitMQ and Riak are built with Erlang.

Leadership

As far as I can tell, Jose Valim and Chris McCord are invested in making the community friendly, approachable for learning and pragmatic. I expect this to continue to trickle down in the rest of the community.

Example of Chris McCord talking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMO28ar0lW8

Language design taste

I’ve found Elixir to be very “tastefully” designed. It cherry-picked the good parts of other languages. A lot of these features are small matters of syntax style or things that could be solved via a library, but one should not underestimate the effect they have on first impression. It’s like visiting a foreign country where everything is new and shiny.

The pipe operator

I first discovered the pipe operator (|>) in F# and it’s by far my favorite operator. All it does is make x |> f the same as f(x). This allows chaining a sequence of transformations, one per line. There’s nothing hard

about understanding how it works, and most people probably already by virtue of using pipes in shell scripting.

Not only are they available in the language, but used upfront in libraries and educational material (the subtitle of Programming Elixir is Functional |> Concurrent |> Pragmatic |> Fun).

Resources: https://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/enumerables-and-streams.html

Built-in unicode strings

A must for languages nowadays, as you can get into extreme pain if it’s not there. The standard library distinguishes between codepoints and graphemes for instance. Interestingly, unicode string handling is implemented as a big macro.

Resources: https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/String.html http://slides.com/chrismccord/elixir-macros#/

Pattern matching

…is one feature from functional languages that makes code clearer and easier to read, less error-prone, comes with built-in compiler optimizations, while being very easy to learn and intuitive all at the same time. Elixir/Erlang go the extra step and allow binary matching binary patterns, which is useful for a lot of parsing tasks.

Resources: https://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/pattern-matching.html http://www.zohaib.me/binary-pattern-matching-in-elixir/

Deeply nested map operations

Accessing things in nested dictionaries is often a pain because you need to check for missing keys at every step. Elixir comes with functionality for that built-in.

Resources: https://dockyard.com/blog/2016/02/01/elixir-best-practices-deeply-nested-maps

IO Lists

Rather than building a string at runtime by a sequence of concatenation, or using boilerplate like StringBuilder, in Elixir you can just give an arbitrarily nested list to IO functions and it’ll flatten them as it outputs them, making string IO super fast.

Resources: http://www.evanmiller.org/elixir-ram-and-the-template-of-doom.html https://www.bignerdranch.com/blog/elixir-and-io-lists-part-1-building-output-efficiently/

Notes on downsides and caveats

One last comment. I’ve already interleaved a few comments on pain points, downsides and caveats throughout this document, but not many. In the interest of avoiding confirmation bias, I tried to actively look for them, but Google has not been helpful so far.

Other interesting use cases and references

Nokia implemented MapReduce in Erlang in a project called Disco, in the days where Hadoop was the only (clunky) option and Spark wasn’t a thing.

A good Erlang reading list: http://spawnedshelter.com/